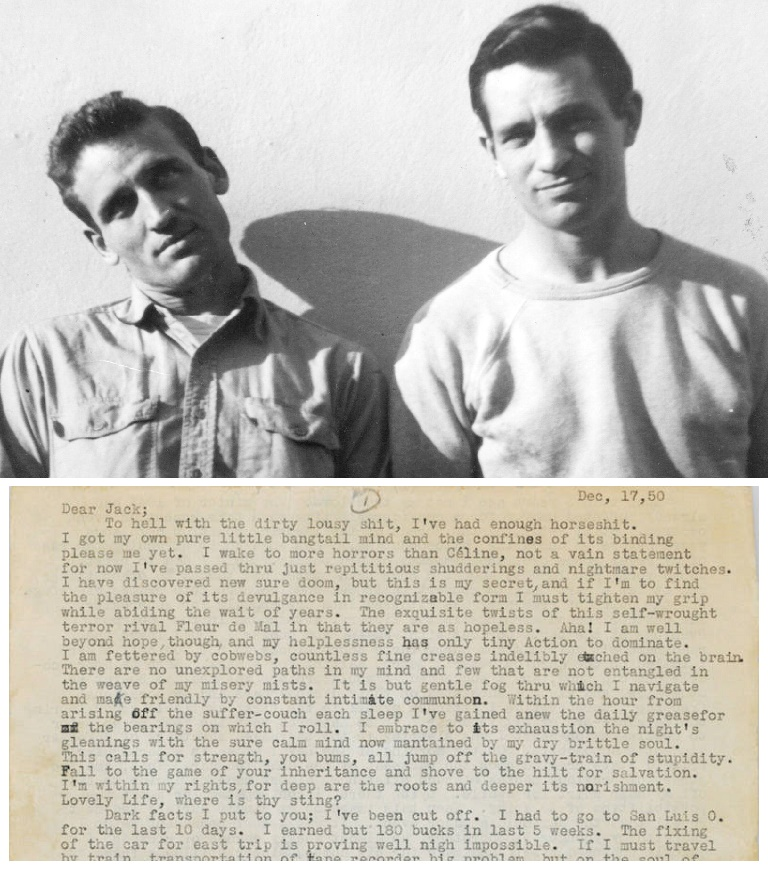

It was sheer coincidence that the letter came to the attention of the Cassady family. Which is to say that without this document, On The Road might never have been written, and without Neal Cassady, Jack Kerouac might have written In My Room, instead of setting the literary world on fire. Written by Neal Cassady in 1950 and lost for 60 years, The Joan Anderson Letter was indeed considered a holy relic of the Beat Generation, and a Rosetta stone document that would show how Cassady’s writing directly influenced Jack Kerouac’s style and direction in life. Jami and Randy are helping carry the torch of Neal’s legacy into the 21st century and are the driving force behind a new book on the “Holy Grail of the Beat Generation,” as the book’s subtitle dubs it, The Joan Anderson Letter. The booth has been setting up on this spot for over a year, and is run by Neal Cassady’s middle child Jami Cassady and her husband of 40 years Randy Ratto. On the sidewalk, nestled between the canopied booth selling used vinyl and a group of strident teenagers putting on a mini-EDM concert, is a tie-dyed folding table full of rare out-of-print books, handmade shirts, cards and the previously mentioned hammer. Part Telegraph Avenue, part Haight Street, it is legendary as a bohemian mecca complete with buskers, charlatans and pop-up merchants. Pacific Avenue has always been the vibrant heart of Santa Cruz. In fact, the more I dug into Cassady’s story, the more it seemed like a story about a time traveler, (as I write this, a truck passes by my window with the word “Moriarty” emblazoned on the side) where the traveler creates his own legends across space and time.

Not only is Cassady the Dean Moriarty character in On The Road, the seminal 1957 novel by Jack Kerouac that launched a generation of pilgrims, travelers and seekers, but his own writing, mostly through letters, may have been more influential than anyone has yet acknowledged. Four decades later, I held Cassady’s hammer in my hand, like Thor without the muscles. It was there and then I began to ingest the stories of the legendary, mysteriously cool Neal Cassady and his hammer-swinging antics. In 1977, I serendipitously stumbled upon a dog-eared copy of Tom Wolfe’s The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. I sought to experience something more meaningful, more transcendent, more damn fun. Every “holiday” focused on consumerism and turning the wheel of capitalism one expensive inch at a time. America, I believed, was bereft of meaningful tradition. “Myths are stories of our search through the ages for truth, for meaning, for significance.” Joseph CampbellĪs a teenager in suburbia in Northern New Jersey in the late 1970s, I was desperate for significance, some sort of a sign that life wasn’t just a cross between Friday Night Lights and The Stepford Wives.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)